Mary Gauthier has never been afraid to tackle the emotional and the personal in her songwriting. In five albums prior to this, she’s taken on issues of love, loss, politics, faith and family problems. But where that last one is concerned, Gauthier had not, until now, fully explored her own history, that of a girl abandoned by her mother at birth and left at an orphanage, before being adopted by a family she would later run away from. Three years ago, Gauthier sought to find her real mother, but when she did so, got only a phonecall and was refused a meeting.

Mary Gauthier has never been afraid to tackle the emotional and the personal in her songwriting. In five albums prior to this, she’s taken on issues of love, loss, politics, faith and family problems. But where that last one is concerned, Gauthier had not, until now, fully explored her own history, that of a girl abandoned by her mother at birth and left at an orphanage, before being adopted by a family she would later run away from. Three years ago, Gauthier sought to find her real mother, but when she did so, got only a phonecall and was refused a meeting.

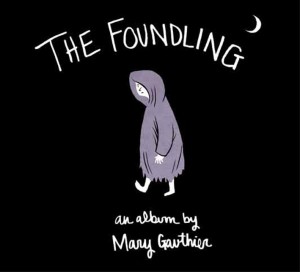

The Foundling tells that story. To do so, it must explore the pain of some deep and lasting wounds, many of which will never heal. But as emotional and affecting as this album is, it is not a miserable affair. Gauthier may have been hurt that her mother refused to meet her, as told in the album’s centrepiece, March 11, 1962, but she has not been discouraged from her efforts to find her identity.

There’s no self-pity here, but instead a note of forgiveness and somewhere, underneath the pain, a lasting love for the mother she never knew. As Gauthier sings in Sweet Words, “I don’t trust my heart anymore/It’s busted open, bruised, beat up and sore/Even while it’s limping around in pain/All I want to do is reach for you again”.

Musically, you might expect a stripped-down sound for such brutal topics but, working with the Cowboy Junkies’ Michael Timmins, Gauthier has used a wide range of styles and instruments to tell the tales, and written some of her best music to date. Indeed, this might be her best album to date – it certainly stands up next to Between Daylight and Dark and Mercy Now – but what cannot be denied is that it already feels like her most important.

Gauthier has been writing songs for 13 years now, and you get the sense everything has been building towards this – the need to tackle the events that most markedly shaped her life. It’s dangerous ground, but Gauthier has navigated it brilliantly.