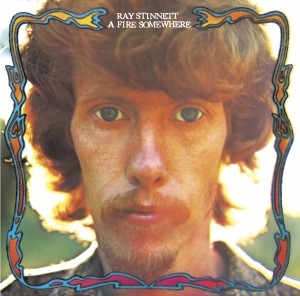

“I MAY HAVE been a little headstrong.” Ray Stinnett can afford a little chuckle when reflecting on why it took 41 years for his album A Fire Somewhere to see the light of day. Putting out any record can be a labour of love, but few of them come with a backstory quite like this.

There’s a cameo from Elvis and a key supporting role from Booker T. Jones, but the central character is Stinnett himself, burned by an early brush with stardom that left him sceptical of the music industry’s promises. The result was a potentially classic psych-folk record that gathered dust for four decades before a chance discovery saw it released this month, emerging like a time capsule from another age.

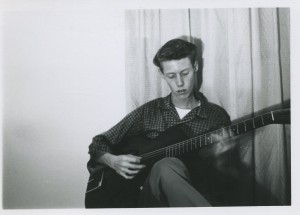

STINNETT’S STORY BEGINS in post-war Memphis where he grew up hooked on music in all its forms. He tried learning the piano at an early age, but it was his Uncle Mickey’s guitar that fascinated him most. He would get his own at the age of 12, and it was on the way home from Nathan Novak’s pawn shop, his Silvertone F-hole by his side on the backseat of mom and dad’s car, that Elvis himself pulled up alongside in a pink Cadillac.

“Hey Elvis,” said young Ray, holding up his new guitar. “Hey Cat,” The King replied.

If he didn’t already, Stinnett now knew what he wanted to do with his life.

“Elvis was definitely an influence in Memphis, and an influence for everyone,” Stinnett said. “We all related with him because that kind of rock ‘n’ roll had gotten on top of the music market but still wasn’t accepted by a lot of adults because of the hip shaking and everything that went with it. He wasn’t only a musical model, but also a model of rebellion, a new creation in pop culture.”

Over the next few years, Stinnett threw himself into music, learning from a teacher who counted Elvis’ guitarist Scotty Moore amongst his friends and could show his student the latest licks. Memphis was a melting pot of young musicians, but Stinnett already had bigger ambitions. While most of the kids his age played for fun, he was already eyeing a career.

“For me, it was about putting gas in my car so I could go and have a life,” he said.

He met a drummer, Jerry Patterson, a couple of years older than him, and the pair began to seek better paying shows around town. Soon their paths crossed with Sam Samudio, a Texas musician who had arrived in Memphis in 1963, and together with a couple of others they formed Sam The Sham & The Pharoahs. When they recorded their first song, ‘Wooly Bully’ , written about Sam’s cat, they had no idea of the whirlwind that was about to sweep them up.

“We worked our butts off and we managed to make it a regional hit,” Stinnett said. “But then it went national.”

‘Wooly Bully’ would eventually sell three million copies, hitting number two on the Billboard charts and earning the young band national tours, television appearances and a brief taste of fame. But it was not to last.

“Our managers thought we were kind of a one-shot wonder with ‘Wooly Bully’ and didn’t really support us,” he said. “The business turned on us. We were used up and thrown away.”

But Stinnett was not as disappointed as you might imagine. He may only have been 21, but he wasn’t too short-sighted to wonder if it was all too good to be true.

“It went pretty fast,” he said. “We didn’t really know where the future would lead us. It was my chosen profession but I had a wife and small child and I knew being a superstar probably wasn’t a sustainable lifestyle.”

The four Pharoahs soon quit, and while Sam found another band, Stinnett and his friends went off to write about their experiences, releasing ‘The Hanging’ and ‘You Sure Have Changed’ as the Violations in 1966. The songs can sound bitter looking back, but that is not how Stinnett remembers those brief glory days.

“It was a wonderful experience,” he said. “All the problems came later but it was marvellous for a time. It was an eye-opener, a mind-broadening experience.”

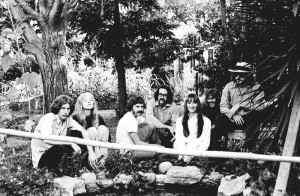

Still searching for a real direction in life, Stinnett moved with his wife Sandra to the famous Morning Star Ranch commune near San Francisco for a time, but the music bug didn’t leave him and it was at this time he put out a single on Capital Records with his latest band 1st Century.

MEMPHIS KEPT CALLING him back, and the couple returned in 1968. It wasn’t long before Stinnett began playing locally with Rita and Priscilla Coolidge, and one Booker T. Jones. He immediately struck up a rapport with the Stax soul man, and by the following year he was recording an album with him.

“We just spent a whole summer in the studio with family and friends dropping in to help,” Stinnett recalled. “That’s Sun Tree and Pepper West which is still unreleased. They declined it, but maybe we’ll release that at some point.”

Soon after, as the Stax hayday came to an end, Booker T. moved west to join A&M records out in California, but he did not forget his friend, and called up Stinnett suggesting he record an album for his new paymasters. The offer came with a budget and real prospects from a top label.

“I had money and I could run with it,” Stinnett said. “Booker T. told me to go back to Memphis. ‘You know what to do,’ he told me. ‘Go on and do it’.”

Stinnett went home and the songs came pouring out of him. Songs about his brush with fame, about his fascination with the cosmos, about his life as a family man. The unique blend became A Fire Somewhere, a record that seemed ready to make Stinnett a star. But that is where the problems began all over again.

“When it was done we took it out there and A&M treated me royally,” Stinnett said. “We did really good for a while but eventually reached an impasse.”

Stinnett had been scarred once before. He was damned if it was going to happen again.

“Maybe I asked for too much creative control,” he said. “Having been managed through ‘Wooly Bully’ I was not a guy who wanted to know what management thought. I wanted to be in control of my own destiny.”

Planned release dates came and went while Ray and his band – who he had promised touring work to – began to get antsy.

“I had these guys in Memphis and I had a promise to them to take it on the road,” he said. “I needed to keep my band together, and I needed to be making some money myself too. It lagged and then when we talked again and we didn’t have a good meeting…They kept saying, ‘We’re going to make you a superstar’. But I didn’t care about that. I just needed to work. We said how about getting us some bookings at the Whiskey A Go Go pre-release or something but they just seemed to get pissed at that.

“They said, ‘You need to get a manager, I don’t want to talk to you, I want to talk to your manager’. I said I didn’t want one and that was the end of the conversation.”

Ray was released from his contract, handed his tapes, and sent on his way.

“There were no hard feelings,” he said. “They were very nice about it.”

With the benefits of hindsight and 40 years of wisdom, Stinnett admits he might have done things a little differently now, but recalls vividly why he had walked away.

“They had pointed to all these gold records on the walls of the office and said, ‘This is what we want for you’,” he said. “But I just wanted my record to come out organically and naturally and take its course. I wanted a sustainable lifestyle and the idea of being a superstar scared me. Perhaps it was the best thing all in all. That’s the way it went down, there’s no point in thinking about what might have happened.”

STINNETT HUNG AROUND Los Angeles for a few weeks, trying to find some interest in his tapes without much success and feeling increasingly like a fish out of water.

“Things were changing fast, we were moving into the excessive 70s,” he said. “Vietnam was dragging on. There was a lot of good and bad, a lot of things were getting fast. There was a lot of cocaine around and that was never my thing. It was too fast for me, and I went back to Memphis.”

Several careers followed while A Fire Somewhere sat silently on a shelf somewhere.

“I had to do a lot of soul searching,” Stinnett said of the years that followed. “We’ve lived a bit of an alternative lifestyle, but at the end of the day the kids had to go to school. I became a carpenter. I figured if it was good enough for Jesus, it was good enough for me. I’ve managed to make a living and picked up a lot of skills, in graphic arts, computers, all sorts really, and I’m using them now.

“I learned to wait, and I’ve learned to prepare while I wait. I’ve just been trying to put all the pieces together.”

But whatever else he was doing, Stinnett never gave up writing, recording and playing music with his friends and family. Eventually so much piled up Stinnett didn’t know what to do with it all.

“I thought about publishing it for others to record, but I couldn’t do it,” he said. “Songs are like children. You want to raise them up. They can go to school and have other friends later. So I’ve hoarded it.”

THE IDEA OF PUTTING the records out never left him. He was considering repackaging some of the songs from A Fire Somewhere for a CD release when he got an email out of the blue from veteran A&R man Jeffrey Weiss. A keen record collector, Weiss said he had come across some of Stinnett’s test pressings and wanted to know more.

“The way the music industry is, there is always something hanging around on a shelf somewhere and sooner or later someone will find it,” Stinnett said. “You just hope it’s someone like Jeffrey.”

Weiss, who had worked at A&M back in the 1970s, put Stinnett in touch with the Light In The Attic label in Seattle, and the wheels were in motion for this month’s release. Stinnett had kept everything, including the original artwork, all these years, and it has all been reproduced exactly as it would have appeared 41 years ago.

“I’m just really pleaed to see it, I’m blown away really,” he said, while admitting the buzz isn’t what it might have been were he still a young man. “It’s still also anti-climatic in a way. I guess I had a lot more energy to burn over the years. I’m not saying I’m burnt out, just a little bit older and a little bit slower. I can’t head out on the road like I would have done, though it would be nice to do a few gigs.”

That said, Stinnett is excited to finally have his record out in the world, admitting to scanning the internet almost daily to monitor the reaction. Having kept it bottled up for four decades, he cannot help but revel in the attention it has received.

“This is my time,” he said. “It’s taken quite a while to arrive. I’ve been waiting for the gates to open so I can run.”