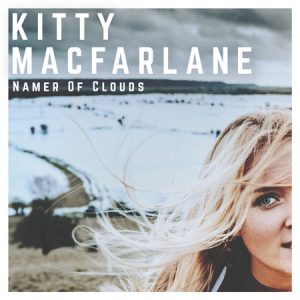

On her debut album Somerset singer-songwriter Kitty Macfarlane presents an occasionally dazzling set of songs that span traditional and contemporary folk, and includes a few numbers that might well deserve a spot among the English folk canon themselves.

The press release that accompanies Namer of Clouds describes Macfarlane as ‘a songwriter and guitarist’, but even across duration of the record it’s clear that she takes on a number of other roles. She is a documentarian, gathering and sharing stories we might otherwise never hear. She is an interpreter of the old folk tradition, performing three new arrangements alongside her own original songs. And, above all, she is a curator who – in the curious form of a folk album – has opened a unique and enthralling museum dedicated to the world around us.

It’s no exaggeration to describe the sensation of listening to Namer of Clouds as akin to walking through a small but lovingly crafted museum. Each song is an exhibit that has been placed carefully not only to bring your attention to the subject at hand – local legends of sea morgans, the flooding of the Somerset Levels – but to highlight how they relate to everything else. The entire world is collected here, placed under a glass bell jar and viewed all at once by a musician who is both fascinated and sympathetic throughout.

The understated album opener, ‘Starling Song’, looks upwards to the pulsating murmurations of birds above the Avalon Marshes. Macfarlane’s gaze remains in the heavens as her second exhibit unfurls – a breathtaking moment of consideration for Luke Howard, the eponymous namer of clouds who, in 1802, formed the cirrus and the cumulus forever in our skies. This title track is a soaring highlight on the record; a song on which everything comes together so perfectly, so effortlessly, as to create in the listener a sense of weightlessness. When the music drops out halfway through we are left to freefall until everything blows back in like a gale and lifts us once more.

Macfarlane makes for a sensitive teller of stories, and her approach at times borders on reverential. ‘Sea Silk’ speaks of ancient crafting traditions from the Sardinian coastline, and in the liner notes Macfarlane writes of meeting ‘the last of the sea silk seamstresses’. The experience is translated into a story not only of the craft, but of sisterhood and tradition passed from generation to generation.

Where often songs like these can feel cynical and forced, as though the songwriter has discovered formulae that reveal the most successful tropes of popular contemporary folk songs, Macfarlane writes with a clear and unbridled passion. She wades in the rivers of her songs, both figuratively and, one senses, literally. Her awe at the experiences of the European Eel is tangible, and the song it yields as moving as any song about eels might ever manage to be again.

Not every exhibit in this museum is without flaws, and the glass case that contains ‘Wrecking Days’ is too brightly lit – the all-in approach to production that worked so well on the record’s title track drowns the superior lyrics here. A baffling guitar solo feels completely out of place. But ‘Wrecking Days’ is, in terms of sheer songwriting, the most effective lyric on the record and one that might easily be revisited by others down the line. Folk is a tradition that passes through generations, one take on a song preceding another. Here is a lyric and melody that deserves to echo for a long time yet.

For an album of such disparate themes to feel so coherent is a remarkable feat. There are morbid trad folk numbers, coming-of-age songs and a lullaby that speaks in the most remarkable terms (“As surely as the rivers reach the oceans/Dawn wages war on the dark”). All albums are, at their most unromantic core, a collection of songs. But rarely has a debut collection been put together with such clarity and confidence, and such exciting promise for the records that might follow.

Words: Stephen Rötzsch Thomas