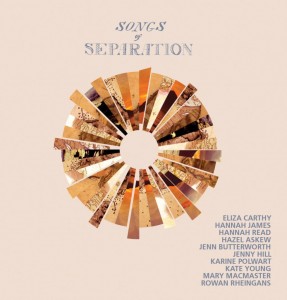

“Separation” is a much broader term than most of us would give it credit for. While it would most certainly immediately be taken on as an inference towards a partition of physical or communicative value, the word could also successfully be applied towards any number of assorted variables, from a cultural separation, a separation between political outlooks, separation from the natural world from the view of the bustling city, and so on and so forth. The various artists of which the Songs of Separation Collective is comprised — Jenny Hill, Eliza Carthy, Hannah James, Hannah Read, Hazel Askew, Jenn Butterworth, Karine Polwart, Kate Young, Mary Macmaster, and Rowan Rheingans — each know this by heart. Formed at the behest of Hill following inspiration from the 2014 Scottish independence referendum, the project spread its encompassing wings through an evolution that came as the ten artists ascended further into their collaboration.

Ultimately, the resort of these ten singer-songwriters working together is a classical folk album that crosses borders in sound between Scottish and British traditions, and beyond, whilst taking into account a myriad of pathways upon which separation can be explained. Most times, more than one type of separation is referred to, and even at once. Such is the case, for example, in opening track “Echo Mocks the Corncrake”. Though it could initially be brushed off as not much more beyond a song of yearning for a lover gone to live in the city, it also takes into account the corncrake, a type of bird, and its kind being forced to live in a smaller, select area of land as the Scottish Industrial Revolution scrapes its claws through the intrinsic beauty spread out by Mother Nature.

Praises can be sung about the work put into preserving the legacy of the world’s traditional folk music in and of itself, but what could initially have been shrugged off as a simple collaborative project focused around covers is given extra layers to rest upon with its unique concept in mind. A worthy, earthy listen in and of itself, the sheer vastness of the concept matter at hand takes a grip of an individual who’s really listening and takes them to a higher place of reflection upon the past hundreds of years of folk music and how, even then, throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, it was a political and romantic movement worthy of an ear.

Words: Jonathan Frahm